Reducing The Risk for ACL Tears with Movement Quality Screening

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) tears are nothing short of soul-crushing. Athletes who suffer one are in for a long 9–12 month ride of surgery concerns, head-scratching post-op differences of opinion, and the potential for insurance companies to prematurely cut them off, resulting in high risk for a re-tear. It is extremely frustrating that we still lack common knowledge about this injury. Especially when we have been seeing such a huge spike in ACL tears in recent years. In America alone, over 200,000 ACL injuries occur each year and 70 percent of them are non-contact. With the advancements in strength and conditioning available to us today, more can be done to reduce the amount of ACL injuries suffered. So much of our time and resources are devoted on what to do after the injury happens. Imagine if we were more proactive and put similar efforts into preventive measures. We need to do better at putting young athletes in a less vulnerable position, and screening can be a great place to start. After screening, young athletes should become introduced to a strength and conditioning program because research has proven that it is the most effective method for reducing one’s chance for suffering this devastating injury.

What is a Non-contact ACL Tear?

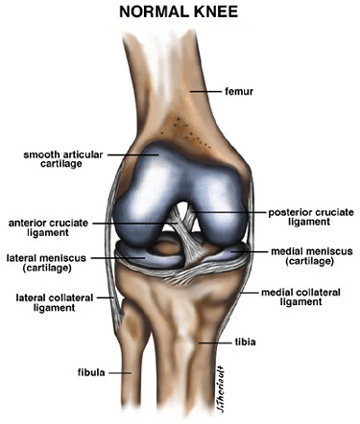

The ACL is a thick band of tissue with two major strands that extend from the lower leg bone (tibia) to the thigh bone (femur). It runs diagonally in the middle of the knee to provide rotational stability.

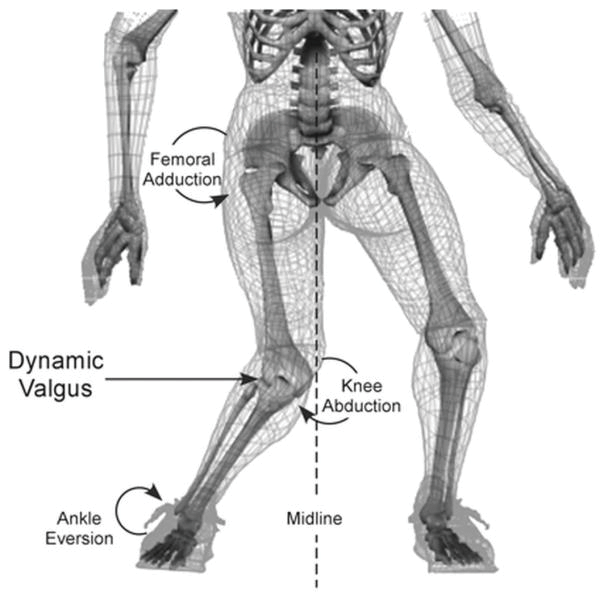

To paint a picture, let’s examine how the ACL functions when we run. When our leg strikes the ground while running, the tibia moves frontward on the femur and then returns to neutral when our leg cycles off the ground. A strong ACL will help keep that forward shift of the tibia in a healthy range throughout the forward stride. When the ACL is injured however, it becomes difficult limiting the forward motion of the tibia. Non-contact ACL tears are common in sports like soccer, basketball, football, and lacrosse because these athletes are constantly cutting, pivoting, decelerating, and re-accelerating. When planting or pivoting, three significant forces are placed on the ACL. These are internal rotation, dynamic valgus, and anterior translation. For untrained individuals whose muscles are weak, or technique is poor, these forces can cause an ACL tear. We know the ACL’s job is to provide stability for the knee in both forward and backward translation, and rotation. But when young athletes whose bodies are still developing are in these fast-paced competitive environments, an ACL tear can happen any given day and the risk is much higher for athletes without strength training experience.

What Can be Done?

Something that I believe should be common practice is for youth coaches to work with strength and conditioning coaches to administer movement screens. There are several different screens used by professionals in the field to assess an athlete’s risk for an ACL injury. Collegiate athletes are fortunate enough to undergo such screenings because they have strength coaches and sports medicine professionals available to them year-round. But what about the fact that almost a third of preteen and teen soccer players sustain ACL tears? If we don’t start putting more effort into setting these young athletes up for success, this epidemic will only continue to get worse. Youth sport participation has been steadily increasing, particularly among females, who are 4-6 times more likely to suffer an ACL tear. As children develop through puberty and undergo their growth spurt, their bodies are growing at such a fast rate that neuromuscular control becomes negatively impacted. Certified strength and conditioning specialists will know what to look for when assessing an athlete’s movement patterns. Common red flags include knee valgus, quad-dominance, poor landing mechanics, weak glutes, weak hamstrings, poor core strength, etc. While not all ACL injuries are entirely preventable, there are certainly ways to reduce the risk. The first preventative step should be to screen our young athletes whose bodies are still growing. There are a multitude of assessments used by professionals across the world who have their own scoring systems in place. But for the sake of assessing the quality of a beginner’s movement patterns, especially if equipment is limited, try these quick and effective drills.

Assessment #1 – Box Jumps

The box jump exercise serves many purposes. It is a great exercise for a multitude of reasons including power and explosiveness, deceleration, triple extension, etc. However, when prescribing exercises, it’s always important to explain “the why” to your athlete. For example, when using box jumps as an ACL injury risk screen, I don’t care how high they jump. I am simply monitoring how they jump and how they land. Check out this video for more information – Box Jump Screen

Assessment #2 – Bounding Variations

Bounding drills are also great and when used for injury risk screens, it follows a similar criterion as box jumps but bounding variations are more sport specific. I am monitoring the quality of their single-leg jumping and single-leg landing mechanics more-so than how far or high they jump. Check out this video for more information – Bounding Screens

Assessment #3 – Drop to Vertical Jump Test

This is a great screen used by many fitness professionals who work with athletes. The athlete stands on an elevated platform (box) and steps off or performs a subtle hop off the box, then performs a vertical jump as soon as they land. Check out this video for more information – Depth Drop to Vertical Jump Screen

Assessment #4 – Dynamic Balance Tests

Neuromuscular control is a major contributing factor for potential ACL injuries. When monitoring an athlete’s ability to maintain their balance, it gives coaches significant insight as to how efficient their central nervous system is with communicating with their body. Improving proprioception (knowing where the body is in space) should be a staple for any athlete’s strength and conditioning program. Check out this video for more information – Dynamic Balance Screening

Michael has been a strength coach at Olympia Fitness and Performance for three years. Michael graduated from Rhode Island College where he studied Community Health & Wellness with a concentration in Wellness & Movement studies. After graduating, Mike went on to get his CSCS (certified strength and conditioning specialist) through the NSCA. He is also a Certified Speed and Agility Coach, as well as a TPI certified coach. In his three years as a strength coach, Mike has helped clients from all walks of life improve their fitness levels. He has a strong passion for helping young athletes not just improve their athletic performance, but also helping them build confidence.

Sources